INTRODUCTION

Should the courts, in judicially reviewing legislation, employ a presumption constitutionality? Should they, in other words, presume that a law enacted by Parliament or the provincial legislatures is constitutionally valid, rebutting that presumption only in the face of convincing evidence? The answer to this question is not as clear as one might suppose.

In the context of the division of powers, there exists a strong presumption of constitutionality. A legislative provision is presumed to be intra vires[1] and the Court ought to approach the question of constitutional validity with the assumption that it was validly enacted.[2] Where the Charter[3] is concerned, however, the Supreme Court has generally taken opposite view. In short, there is no presumption of constitutionality.[4] As the Supreme Court explained in Manitoba v. Metropolitan Stores, the “nature”[5] of the Charter – and specifically its “innovative and evolutive character”[6] – renders it incompatible with a presumption of constitutionality.[7] Yet, as we shall see, the Supreme Court has allowed for a more limited presumption of constitutionality in the Charter context.

The 35th anniversary of the enactment of the Charter is fast approaching, and this would seem as good a time as any to re-examine and re-evaluate the presumption of constitutionality, specifically as it relates to the Charter. In the following paper, I do just that, and argue that the presumption ought to apply with equal rigour in the context of the Charter. In Part I, I discuss the history of the presumption of constitutionality in the Canadian tradition, and the way in which the principle has been largely discarded when it comes to Charter adjudication. In Part II, I make the case for a presumption of constitutionality in the Charter context. I argue that the presumption of constitutionality has entered a paradoxical state, in that it is simultaneously both alive and dead. Affirming the presumption now in the Charter realm would not be incompatible with the nature of the Charter or the way in which the Charter has been interpreted. I conclude by very briefly discussing how a presumption of constitutionality in Charter adjudication might operate in practice.

THE PRESUMPTION OF CONSTITUTIONALITY IN THE CANADIAN TRADITION

The presumption of constitutionality in Canada can be traced to Justice Strong’s dissenting opinion in Severn v. The Queen.[8] Severn was one of Canada’s first federalism decisions and Strong J. emphasized that, despite its implied power of judicial review[9], the Court should always presume that a democratically enacted law is constitutionally valid:

As this Court is now, for the first time, dealing with a question involving the construction of that provision of the British North America Act which prescribes the powers of the Provincial Legislatures, I do not consider it out of place to state a general principle, which, in my opinion, should be applied in determining questions relating to the constitutional validity of Provincial Statutes. It is, I consider, our duty to make every possible presumption in favor of such Legislative Acts, and to endeavor to discover a construction of the British North America Act which will enable us to attribute an impeached Statute to a due exercise of constitutional authority, before taking upon ourselves to declare that, in assuming to pass it, the Provincial Legislature usurped powers which did not legally belong to it; and in doing this, we are to bear in mind ‘that it does not belong to Courts of Justice to interpolate constitutional restrictions; their duty being to apply the law, not to make it.’[10]

One year later, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council similarly stated that it “is not to be presumed that the Legislature of the dominion has exceeded its powers, unless upon grounds really of a serious character.”[11] The lower courts followed suit. In 1890, Burton J.A. of the Ontario Court of Appeal echoed Strong J.’s admonition that “every possible presumption” must be made in favour of the validity of legislation, and added that this presumption was “not to be overcome, unless the contrary is clearly demonstrated.”[12]

In 1898, the great Canadian legal scholar, A.H.F. Lefroy published The Law of Legislative Power in Canada,[13] setting out sixty-eight general propositions regarding the then BNA Act, 1867 (now the Constitution Act, 1867). Proposition 18 summarized the presumption of constitutionality as follows:

It is not to be presumed that the Dominion Parliament has exceeded its powers, unless upon grounds really of a serious character; and so, likewise, in respect to Provincial statutes every possible presumption must be made in favour of their validity.[14]

Thus, by the end of the 19th century, the presumption of constitutionality had already become a firmly entrenched principle of constitutional interpretation.

The justification for the presumption of constitutionality lay in its implicit respect and regard for Canada’s democratic character and institutions. The presumption expressed the idea that constitutional interpretation was primarily the purview of the courts, though not exclusively so, and that democratic legislatures, always mindful of the limits to their constitutional authority, would not intend to overstep their jurisdiction.[15] No one seriously questioned the authority of the judiciary to strike down unconstitutional legislation – and indeed the Supreme Court and the Privy Council did so with some regularity during the first century following Confederation as guardians of the Constitution’s “watertight compartments”[16] – but that authority was tempered by a good measure of deference and humility.

In his dissent in Felipa v Canada, Stratas J.A. of the Federal Court of Appeal put it this way:

In our constitutional framework, the courts are responsible for making the final decisions on constitutional interpretation. They are duty-bound to strike down legislative and executive actions and practices that are wrong, even where they are longstanding and consistently followed. But we must recognize that these other branches of government do try, as they must, to keep their actions and practices within the limits of the powers given to them under the Constitution. This involves making judgments, implicitly or explicitly, regarding the limits in the Constitution. Other branches of government are interpreters of the Constitution.[17]

With the enactment of the Charter in 1982, the presumption of constitutionality has taken on a dual reality. It continues to apply with as much vigour as ever in the division of powers context,[18] but it appears to carry no weight in Charter adjudication. The early Charter case, Metropolitan Stores, tackled the presumption of constitutionality head on and concluded that it was “positively misleading” where legislation was being challenged under the Charter.[19] As stated in the introduction to this paper, the Court concluded that the presumption was fundamentally contrary to the nature of the Charter, and in particular its “innovative and evolutive” character.[20] Writing on behalf of the Court, Beetz J. explained that Charter rights are not frozen in their content, and must remain “susceptible to evolve in the future.”[21]

The Court, however, left open the question of whether a more limited presumption of constitutionality was compatible with the Charter.[22] Generally, the presumption of constitutionality refers more specifically to a presumption of constitutional validity – meaning that the Court presumes a law to be constitutionally valid. But there is another meaning to the presumption of constitutionality, which may be more appropriately described as a presumption of constitutional construction.[23] This presumption hold that if a statutory provision is capable of two interpretations, one that is constitutional and one that is not, the courts should choose the construction that conforms with the Charter.[24] Following the Manitoba Stores decision, the Court has continued to reject a presumption of constitutional validity, while repeatedly endorsing the presumption of constitutional construction.[25]

But even this is not the entire story. The basic distinction between the presumptions of constitutional validity and constitutional construction is that the latter does not necessarily require deference to the legislature. The presumption of constitutional construction could theoretically be justified solely on grounds of expediency. If a law is subject to two plausible interpretations, then it makes eminent sense to choose the one that is constitutional, since this saves the time and resources associated with re-enacting the law. Thus, it would not be inconsistent for the courts to reject a presumption of validity while affirming a presumption of constitutional construction, provided the presumption of constitutional construction was rooted in a concern for expediency and efficiency. Yet, the presumption of constitutional construction has routinely been justified on what might be called philosophical or democratic grounds – on the basis that Parliament and the legislatures intended to adopt Charter-compliant legislation.[26] If we accept that Parliament and the legislatures intend to enact legislation in conformity with the Charter, it surely follows that their attempt to do so should entitle them to some deference at the outset of a Charter inquiry.

This is precisely the logical leap the Supreme Court made in R. v. Ruzic. In that 2001 decision, the Supreme Court re-affirmed the presumption of constitutional construction, but it also implicitly affirmed a quasi-presumption of validity. The Court noted that while the issue of deference to the legislature’s policy choices is ordinarily considered at the s.1 stage, it was appropriate to grant the legislature “some latitude” at the outset of the Charter inquiry given the presumption of constitutionality, which “is based on the notion that Parliament intends to adopt legislation that is consistent with the Charter.”[27] These comments could admittedly be considered obiter dicta, and, to be sure, there is no indication that the Court has overturned its decision in Metropolitan Stores. What is clear, however, is that the presumption of constitutional construction cannot be readily divorced from the presumption constitutional validity. They are, in practice, two sides of the same coin, and the Supreme Court’s affirmation of one and rejection of the other has left the doctrine in a state of confusion.

SOLVING THE PARADOX

The presumption of constitutionality has deep roots in Canadian constitutional history and is borne out of deference to this country’s parliamentary traditions. In recent decades, however, it has become paradoxical, applying to a part of the Constitution but not to the Constitution in its entirety. The implication is that our legislators have the constraints of the Constitution foremost in their minds as they consider matters of jurisdiction, but then abandon all consideration of the Constitution when the issue turns to individual rights. If we take the example of Canada’s new medically-assisted dying law, the courts are to presume that members of Parliament laboured to ensure that the law did not encroach upon the provincial power over property and civil rights, but at the same time were either unaware of, or did not care, what impact the law would have upon life, liberty and security of the person.

The implicit argument in Metropolitan Stores is that the Charter is somehow different. It does not simply confer legislative jurisdiction or establish a structure of government; it deals with sacred individual rights. However, there is no indication in the Charter itself (nor in any other provision of the Constitution) that the Charter represents a fundamental departure from other parts of the Constitution.[28] And indeed, the Supreme Court has confirmed that the Charter holds no special status within the Constitution; a Charter right does not trump another constitutional provision.[29] At base, Charter rights are simply an extension of the limits already imposed upon legislative jurisdiction in the Constitution Act, 1867. The division of powers and the Charter both set out what the state cannot do (and in some cases what it must do). Both, in other words, deal with matters of jurisdiction. The Constitution Act, 1867 typically deals with jurisdiction over economic matters, but there are a number of federalism cases concerning individual rights such as freedom of expression, freedom of religion, and security of the person, most notably where a province has sought to enact legislation that is, in pith and substance, criminal law.[30]

Metropolitan Stores also suggests the Charter is distinct because its provisions are “susceptible to evolve in the future.”[31] Once again, however, there is nothing unique about the Charter in this regard. The Supreme Court has affirmed that the living tree doctrine applies to the entire Constitution, including the division of powers.[32] In fact, the Supreme Court first employed the living tree metaphor in the federalism context.[33] The notion that the “the interpretation of [the division of] powers and of how they interrelate must evolve and must be tailored to the changing political and cultural realities of Canadian society” has not undermined the presumption of constitutionality in the federalism context; and there is no reason why the “evolutive” character of the Charter ought to preclude a presumption of constitutionality in that realm.

Moreover, to the extent that Charter rights ought to evolve with time, there is arguably an even greater justification for a robust presumption of constitutionality. Charter rights are said to be evolutive so that they can remain current with new social and economic circumstances – what the Supreme Court has called the “realities of modern life.”[34] Assuming this to be the case, it does not follow that the courts are in the best position to discern what those “realities” are, and what impact they ought to have on individual rights. Arguably, Canada’s elected representatives are far better institutionally situated than are the courts to determine whether and to what extent times have changed. This, of course, does not mean that the courts should simply bow to the will of the legislature; but nor should the Charter’s “innovative and evolutive” character provide a justification for abrogating the presumption of constitutionality. On the contrary, it provides a justification for reaffirming and reinforcing that presumption.

It could be argued that Metropolitan Stores was correct to the extent it applied to legislation enacted prior to the Charter.[35] Metropolitan Stores was handed down in 1987, just five years after the Charter came into force, at a time when most of the laws on the books had been enacted prior to the Charter’s adoption. Naturally, those who voted on pre-Charter laws could not have conceived of their Charter obligations at the time. This argument, however, is problematic for two reasons.

First, the Charter was not enacted in a vacuum. Many Charter rights were derived from Canada’s common law heritage, not to mention the Canadian Bill of Rights,[36] and the most transformative section of the Charter – s.15, which guaranteed new equality rights[37] – did not come into force until 1985. As Beetz J. acknowledged, the operation of s.15 was delayed three years “presumably to give time to Parliament and the legislatures to prepare for the necessary adjustments.”[38] Beetz J. cited s.15’s operational delay in support of his argument that Charter rights were innovative and thus beyond the contemplation of Parliament and the legislatures. But the inference, in my view, would seem to go the other way. The implication of s.32(2) of the Charter, which states that s.15 shall not come into force for three years,[39] is that the laws in operation at that time already complied, more or less, with the other provisions of the Charter (since there was no need for a delay provision in respect of the other Charter rights), and that within three years, Parliament and the legislatures would have had sufficient time to ensure that those same laws were brought into harmony with s.15.

Second, even acknowledging for the moment that the Charter’s expansive nature would have made it impossible for pre-Charter legislators to attempt to comply with its provisions, 35 years have now passed since the Charter’s enactment. Surely it is the case that Parliament and the legislatures have had ample time to revisit all pre-Charter legislation to ensure conformity with the Charter. Thus, even if Metropolitan Stores was correct when it was decided 30 years ago, it is no longer correct today. Respectfully, the decision should be overturned.

In any case, as discussed above, the precedential value of Metropolitan Stores is ambiguous. The Supreme Court has not reaffirmed the decision in over a decade,[40] and, in the interim, various panels have applied the presumption of constitutional construction to the Charter, acknowledging that Parliament and the legislatures “intended to enact legislation in conformity with the Charter.”[41] Indeed, one panel even acknowledged that this presumption militates in favour of some deference at the outset of a Charter inquiry,[42] which is strikingly similar if not indistinguishable from a presumption of constitutional validity. Overturning Metropolitan Stores now would do nothing more than take these more recent decisions to their logical conclusion: that since Parliament and the legislatures intend to comply with the Charter, we should presume they have done so.

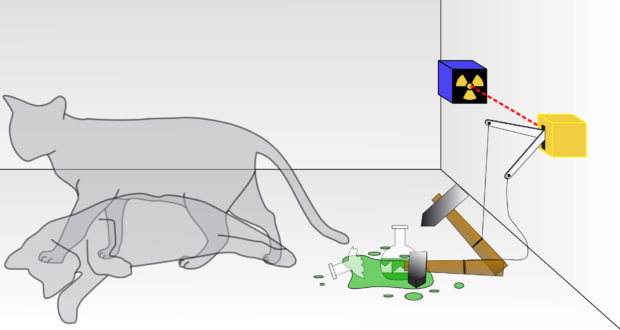

The presumption of constitutionality has become a practical paradox. Like Schrödinger’s Cat, the famous quantum mechanics thought experiment in which a cat placed in a sealed box is simultaneously both alive and dead, so too does the presumption of constitutionality now inhabit a dual state of existence and non-existence. But unlike Schrödinger’s Cat and other logical paradoxes, the paradoxical presumption of constitutionality can be solved quite easily without resort to advanced mathematics or quantum physics. It requires a mere course correction at the Supreme Court of Canada – a simple affirmation that this age-old presumption ought to apply equally to all provisions of the Constitution.

CONCLUSION: APPLYING THE PRESUMPTION

In this paper I have argued that the presumption of constitutionality (and more particularly, the presumption of constitutional validity) has taken on a paradoxical character, in that it applies vigorously in the federalism realm, but has been rejected in the Charter realm. This presumption is well-established in the Canadian tradition, and in my view, there is no principled basis to exclude it where legislation is being challenged under the Charter.

But this naturally raises another question: what would affirming the presumption of constitutionality in the Charter context look like in practice? Would the Court simply pay it lip service and get on with business as usual, or would the presumption form a meaningful hurdle for applicants to overcome in seeking to strike down democratic legislation? And if it were given its due, how would that affect Charter jurisprudence? These questions can only be answered with the fullness of time, but as a starting point, I would suggest that the presumption ought to apply in exactly the same fashion as it does (or should) in the federalism context, namely that “every possible presumption” would be made in favour of the legislation, and only infringements of a “serious character” would cause the presumption to be overturned.[43] It would mean that those cases that typically lie at or close to the margins would be resolved at the outset in favour of upholding the legislation.

By the same token, a presumption of constitutionality could also mean greater protection for core individual rights. There is a tendency at present, especially in the context of s.2 of the Charter, to do most of the “heavy lifting” at the s.1 stage. This is often problematic, as the Oakes test places a great deal of discretion in the hands of judges to balance rights against state interests. And while “core” rights are treated as more deserving of protection, this amounts to a difference of degree not kind (and indeed the Oakes test has been criticized for the degree of discretion it places in the hands of the judiciary regarding social policy matters[44]). A robust presumption of constitutionality would return the meat of the analysis to the right itself. It would mean that only serious rights infringements get in through the front door, as it were, and would arguably necessitate a greater government justification at the s.1 stage. This could mean a more streamlined and doctrinal s.1 analysis in which like cases are treated alike, and the bar for what constitutes “a pressing and substantial concern” and “minimal impairment” is raised to meet the gravity of the Charter breach.

There are, of course, any number of ways a presumption of constitutionality could operate in practice. My aim in this short paper has not been to set out a comprehensive framework for Charter analysis, but rather to make the case for how such an analysis ought to begin; that is, from a posture of deference to Canada’s legislators who “try, as they must, to keep their actions and practices within the limits of the powers given to them under the Constitution.”[45] A presumption of constitutionality is ultimately a presumption legislative competence and integrity; it grants our elected representatives the benefit of the doubt that they are, in fact, “honourable members,” upholding their oaths and striving to act within the bounds of the law. A cynic would say this is far too generous a presumption to make. But if we are to have faith in the viability of our democratic institutions over the next 35 years, and beyond, then such a presumption becomes absolutely necessary.

Notes

[1] Rogers Communications Inc v Châteauguay (City), [2016] 1 SCR 467 at para 81 [“Rogers Communication”].

[2] Nova Scotia Board of Censors v. McNeil, [1978] 2 SCR 662, at 255. See also generally Joseph E. Magnet, “The Presumption of Constitutionality” (1980) 18 Osgoode Hall LJ 87 at 116-121.

[3] Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (U.K.), 1982, c11 [the “Charter”].

[4] R. v. Zundel, [1992] 2 S.C.R. 731 at para 37; See also Manitoba (Attorney General) v Metropolitan Stores (MTS) Ltd., [1987] 1 SCR 110 at paras 16-23 [“Metropolitan Stores].

[5] Ibid at para 21.

[6] Ibid at para 23.

[7] Ibid at paras 16-23.

[8] Severn v. The Queen (1878), 2 SCR 70, at 103 [“Severn”].

[9] See Marbury v Madison, 5 US 137 (1803): “If courts are to regard the Constitution, and the Constitution is superior to any ordinary act of the legislature, the Constitution, and not such ordinary act, must govern the case to which they both apply.” With the enactment of the Constitution Act, 1982, judicial review is now expressly provided for under s. 52(1), which states that any law that is inconsistent with a provision of the Constitution is “to the extent of the inconsistency, of no force or effect.” However, this section is arguably superfluous since judicial review is a necessary function of a political order that places constitutional constraints on government power. Prior to 1982, there was no question that the courts could strike down laws that offended the provisions of the BNA Act. During the Confederation Debates, there was some concern regarding how Parliament’s power would be kept in check. George-Étienne Cartier explained that “the courts of justice will decide all questions in relation to which there may be differences between the two powers…Should the general legislature pass a law beyond the limits of its functions, it will be null and void pleno jure.” See Janet Ajzenstat, Paul Romney, Ian Gentles & William D. Gairdner, eds., Canada’s Founding Debates (Toronto: Stoddart, 1999) at 311.

[10] Severn, supra note 8 at 103 [Emphasis Added]

[11] Valin v Langlois, [1879] JCJ No 1 at para 2.

[12] R v Wason, [1890] OJ No. 50 at para 57 (CA).

[13] AHF Lefroy, The Law of Legislative Power in Canada (Toronto: Toronto Law Book and Publishing Company, 1897).

[14] Ibid, at xxii, 260-269.

[15] Reference re The Farm Products Marketing Act, [1957] SCR 198 at 255. See also Reference Re Reciprocal Insurance Act, 1922 (Ont.), [1924] JCJ No. 1 at para 25.

[16] Reference re Weekly Rest in Industrial Undertakings Act (Can.), [1937] JCJ No 5 at para 15.

[17] Felipa v Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), [2012] 1 FCR 3 at para 159.

[18] Rogers Communications, supra note 1 at para 81.

[19] Metropolitan Stores, supra note 4 at para 15.

[20] Ibid at para 15.

[21] Ibid at para 21.

[22] Ibid at para 26.

[23] See ibid at para 26, which refers to this presumption as a “rule of construction.”

[24] R. v Sharpe, [2001] 1 SCR 45 at para 33 [“Sharpe”].

[25] See Sullivan, Driedger on the Construction of Statutes (3rd ed. 1994), at 322-27; R. v Ruzic, [2001] 1 SCR 687 at para 26 [“Ruzic”].

[26] Sharpe, supra note 24 at para 33; see also R. v Ahmad, [2011] 1 SCR 110 at paras 28, 32.

[27] Ruzic, supra note 25 at para 26.

[28] Section 52(2) of the Constitution Act, 1982 enumerates the various statutes comprising the Constitution of Canada, and gives no indication that the Charter is in any way distinct or that its provisions are somehow on a higher philosophical plain than the rest of the Constitution. Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (U.K.), 1982, c11, s.52(2).

[29] Reference re Bill 30, An Act to Amend the Education Act (Ont), [1987] 1 SCR 1148 at para 62.

[30] See Saumur v City of Quebec [1953] 2 SCR 299; Switzman v Elbling, [1957] SCR 285; R v Morgentaler, [1993] 3 SCR 463.

[31] Metropolitan Stores, supra note 4 at para 21.

[32] Canadian Western Bank v Alberta, [2007] 2 SCR 3 at para 23.

[33] Reference re Regulation and Control of Radio Communication, [1931] SCR 541 at 546.

[34] Reference re Same-Sex Marriage [2004] 3 SCR 698 at para 22.

[35] See, for example, B Slattery, “A Theory of the Charter” (1987) 25:4 Osgoode Hall LJ 701 at 722-723.

[36] Canadian Bill of Rights, SC 1960, c 44.

[37] Charter, supra note 3, s.15.

[38] Metropolitan Stores, supra note 4 at para 18.

[39] Charter, supra note 3, s.32(2).

[40] The last decision that appears to have explicitly affirmed the rule from Metropolitan Stores is Tabah v

Quebec (Attorney General), [1994] 2 SCR 339 at para 24.

[41] Sharpe, supra note 24 at para 33.

[42] Ruzic, supra note 25 at para 26.

[43] See Lefroy, supra note 13 at xxii, 260-269.

[44] The Honourable Justice David Stratas, “Decision-Making under Section 1 and the Legitimacy of Charter Adjudication: Towards a Better Approach” (Lecture delivered at University of Ottawa, April 2012) online YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r7zloQFQhkQ.

[45] Felipa, supra note 17 at para 159.

Advocates for the Rule of Law

Advocates for the Rule of Law

One comment

Pingback: The Advocates’ Quarterly Publishes “The Paradoxical Presumption of Constitutionality” | Advocates for the Rule of Law