Personal injury litigation has come under the microscope over the last few months. Numerous articles have been written criticizing the conduct of personal injury lawyers, specifically with regard to advertising and fees. Most recently, MPP Michael Colle has put forward a private member’s bill that would require every personal injury advertisement to be approved by the Law Society, cap contingency fees at 15%, and outright prohibit referral fees.

Bill 103 is undoubtedly a well-intended measure to address a very real problem in our profession. But with the greatest respect to Mr. Colle, his bill is grossly excessive and would only harm those it seeks to protect: personal injury litigants. It offers a blunt instrument to a problem that requires surgical precision.

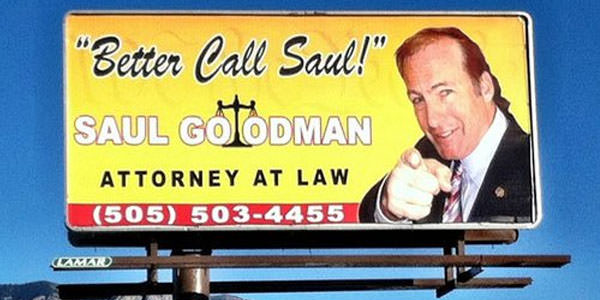

Let’s start with the advertising provisions. Few would doubt that there is a problem in our profession with misleading advertising (and indeed, the personal injury bar was talking about this issue long before it became a hot topic in the media). But Bill 103’s solution goes much too far. It would impose upon the Law Society the impossible burden – given their current mandate and funding – of vetting and scrutinize each and every personal injury advertisement.

The Rules of Professional Conduct, which govern the legal profession in Ontario, already prohibit advertising that is likely to mislead or confuse the public, and the rules governing advertising were amended just this past February to add even more onerous regulations. The Law Society can and should discipline those lawyers who do not advertise in accordance with the Rules. But it is nonsensical to expect the Law Society to become a proactive police force, preventing infractions before they occur. The financial costs of enforcement would be enormous and many good lawyers with ethical advertisements would get stuck behind a wall of red tape.

The proposed contingency fee cap is equally foolish. Billing by contingency (meaning that the lawyer is paid a percentage of the settlement or judgment rather than an hourly rate) ensures that injured plaintiffs who would otherwise be unable to afford a lawyer can get one. We hear and read a lot about the problems with “access to justice,” and while this may certainly be an issue in the criminal and family law realms, it is virtually non-existent in personal injury litigation. We have contingency fees to thank for that.

On the other hand, contingency fees should not be boundless. Most personal injury lawyers I have spoken with agree that a cap is necessary to protect the interests of injured plaintiffs. The problem with Mr. Colle’s proposal is not that it seeks to impose a cap, but that the cap is too low to make commercial sense. A 15% cap would barely cover a lawyer’s overhead and would force most firms to reject all except the most severely injured victims. By contrast, a cap of 30-35% is entirely reasonable. It would provide lawyers with a good incentive to try difficult cases, while also ensuring that accident victims keep the majority of a settlement or judgment award.

The final problem Bill 103 seeks to tackle – referral fees – is the least reported, but probably the most pressing. Too many injured plaintiffs are referred to another law firm without their knowledge, let alone their consent. And where the plaintiff does consent, he or she often has an incomplete understanding of the terms of the referral. Mr. Colle is right to flag referral fees as an issue, but once again, his proposal for a complete ban overshoots the mark. Most litigants have no idea who can best represent their interests, and referrals help ensure that they are paired with a knowledgeable and experienced lawyer who has capacity to take on their claim. It is entirely appropriate to permit lawyers to recover fees for their referrals provided certain conditions are met. First, the client must consent to the referral and understand its terms. Second, the lawyer receiving the referral must have the requisite knowledge and experience to take on the claim. Third, there should be no upfront referral fees – lawyers should not be permitted to “buy” files from one another. The fee must be paid at the conclusion of the action. Fourth, referral fees should be capped in the range of 10-20% of the contingency fee.

* * *

Lawyers are not merely entrepreneurs with a license to practice law. We are, first and foremost, professionals. The duty we owe to our clients is not simply transactional; it is fiduciary. The values of access to justice and freedom to contract must therefore always be balanced against the integrity of the justice system. The fundamental problem with Bill 103 is not that it seeks to strike that balance, but that it would severely upset a balance that has, for the most part, already been struck.

The Ontario legislature has wisely delegated the regulation of the legal profession to the Law Society of Upper Canada, an organization that has existed since 1797. The Law Society has never shied away from its mandate and, as recently as this past February, its Professional Regulation Committee drafted a comprehensive report to address these very issues. This report was based on extensive research and consultation with lawyers across the province, and its recommendations are far more nuanced than the extreme provisions of Bill 103. The timing of Bill 103 just one month after this report was released suggests that Mr. Colle was either unaware of the steps the Law Society was already taking to combat unethical practices, or, worse, didn’t care.

The Ontario legislature should reject Bill 103 and should defer to the body that has competently regulated the profession for over two centuries. The public – and injured people especially – will not benefit from an overly zealous law that shows little regard for how the practice of law and the administration of justice actually work.

Advocates for the Rule of Law

Advocates for the Rule of Law